Our Review

Mikhail Bulgakov spent twelve years writing The Master and Margarita, and he knew he would never see it published. He worked on it in secret in Stalinist Moscow, revised it on his deathbed in 1940, and died entrusting the manuscript to his wife with the words: "It may be of use to someone." He was right. It took twenty-six years, but when the novel was finally published in a censored magazine edition in 1966, it detonated like a bomb in Soviet literature and has been reverberating ever since.

The novel begins when the Devil arrives in Moscow. He calls himself Woland, and he is accompanied by a retinue that includes a giant cat named Behemoth who walks on his hind legs, drinks vodka, and rides the tram; a fanged assassin named Azazello; and a naked witch named Hella. Woland proceeds to expose the corruption, greed, and spiritual emptiness of Moscow's literary and political establishment through a series of increasingly unhinged magical spectacles — a variety show that rains money on the audience, an apartment that devours its inhabitants, a severed head that continues to talk.

Interwoven with this Mephistophelian carnival is a retelling of the story of Pontius Pilate and Yeshua Ha-Notsri (Jesus), written by the Master, a broken novelist who has been driven to destroy his own manuscript and commit himself to an asylum. Margarita, his lover, makes a deal with the Devil to rescue him.

The result is a novel that operates on at least three levels simultaneously — satire, theology, and love story — and manages to be wildly funny, deeply moving, and philosophically profound all at once.

Why This Book Earned Its Place in the Top 100

The Master and Margarita earns its place because it is one of the most audacious acts of literary resistance ever committed to paper. Bulgakov wrote a novel about the Devil visiting Moscow at a time when simply owning the wrong book could get you sent to the gulag. He mocked the Soviet literary establishment, satirized government bureaucracy, and retold the story of Christ's crucifixion — all under a regime that censored religion and executed writers. The courage alone would justify the novel's reputation. That it also happens to be brilliantly entertaining is almost miraculous.

The novel also earns its place because it defies every category. It is a comedy, a tragedy, a fantasy, a love story, a biblical retelling, and a philosophical argument — sometimes on the same page. Bulgakov moves between registers with the ease of a magician pulling scarves from a hat, and the transitions feel not chaotic but orchestrated.

The love story between the Master and Margarita is, paradoxically, the novel's quietest and most powerful element. In a world of Devils and miracles, their devotion to each other is the most supernatural thing of all. Margarita's willingness to fly naked over Moscow and host Satan's ball to save the man she loves is one of literature's great acts of defiant, unreasonable love.

Who Should Read This Book

- •Anyone who loves magical realism and wants to explore its Russian roots — Bulgakov's fusion of the supernatural and the satirical predates and rivals García Márquez.

- •Readers interested in Soviet history — the novel is the most entertaining introduction to the absurdity and terror of Stalinist Moscow you will ever find.

- •Fans of dark comedy — Behemoth the giant cat alone is worth the price of admission, and the satire is wickedly precise.

- •Lovers of ambitious, multi-layered fiction — the interweaving of the Moscow and Pilate narratives is a structural achievement of the highest order.

- •Anyone who believes that art can outlast tyranny — Bulgakov's life and this novel are proof.

Key Themes and Takeaways

- Art and censorship

- The Master's destruction of his manuscript mirrors Bulgakov's own experience, and the novel insists that great art cannot be permanently suppressed.

- Good, evil, and their interdependence

- Woland argues that without evil there can be no good, and the novel explores this paradox with genuine philosophical seriousness beneath its comedy.

- Cowardice as the greatest sin

- Pilate's failure to save Yeshua is presented as the foundational moral crime — the refusal to act on what one knows to be right.

- Love as redemption

- Margarita's love for the Master is fierce, sacrificial, and ultimately powerful enough to transcend the boundaries of the natural world.

- The absurdity of bureaucracy

- Soviet Moscow's literary committees, housing offices, and cultural apparatchiks are satirized with a precision that makes the comedy timeless.

- Truth and power

- Both the Pilate narrative and the Moscow narrative ask what happens when truth confronts power — and what it costs to speak or to remain silent.

Cultural and Historical Impact

Written between 1928 and 1940, The Master and Margarita was first published in a censored version in the Soviet magazine Moskva in 1966-67, twenty-six years after Bulgakov's death. The complete text was not published in Russia until 1973. It has since been translated into dozens of languages and sold millions of copies worldwide. The novel is widely considered the greatest Russian novel of the twentieth century. It has been adapted into films, television series, stage productions, and even a rock opera. The Rolling Stones' "Sympathy for the Devil" was directly inspired by the novel. A bench on Patriarch's Ponds in Moscow, where the novel's opening scene takes place, has become a literary pilgrimage site. The novel's most famous line — "Manuscripts don't burn" — has become a universal declaration of art's survival over censorship.

Notable Quotes

“Manuscripts don't burn.”

“What would your good do if evil didn't exist, and what would the earth look like if all the shadows disappeared?”

“Cowardice is the most terrible of vices.”

If You Loved The Master and Margarita, Read These Next

Ready to read The Master and Margarita?

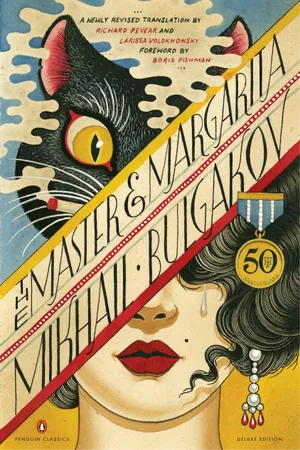

Penguin Classics · 412 pages

Buy The Master and Margarita on Amazon